In “What is propaganda?“, a definition was established followed by a claim. The definition,

“Propaganda is the use of symbols, repetition, and various appeals by marketers, advertisers, and information brokers to sell products, people, and ideas to the public without the use of physical coercion.”

And the claim,

“Essentially, every media input that is consumed through the senses is propaganda.”

How dare you

There is a natural hesitation, or even aversion, to this claim because it pushes against any number of cultural truisms, or “the type of beliefs… culturally regarded as being truisms almost beyond debate.”[1] These are beliefs in, for example, an objective truth, integrity in journalism and the press, or that propaganda is bad and something only other countries do. These types of truisms are at the roots of the public trust. And trust is important to society. It is so important that the mere appearance of trust will do. Appearance is everything.

Another hesitation, or aversion, to the claim is the accusatory nature of suggesting that, well, if all media is propaganda then it implicates everyone that produces media as a propagandist. That’s only an issue if propaganda is negatively defined, but as previously explored, it is a neutral term. So there is no needed complicity in this regard by any participants required.

Just because someone calls themselves a propagandist doesn’t mean they are bad; and just because someone doesn’t like to be called a propagandist doesn’t mean that they are not.

Logos, Ethos, Pathos

Rhetorical persuasion is the algorithm of propaganda. And rhetorical persuasive writing is at the core of academic composition. Rhetoric as defined by Merriam-Webster’s[2] is:

: the art of speaking or writing effectively: such as

a : the study of principles and rules of composition formulated by critics of ancient times

b : the study of writing or speaking as a means of communication or persuasion

2a : skill in the effective use of speech

b : a type or mode of language or speech also

: insincere or grandiloquent language

3 : verbal communication : discourse

Everybody learns rhetoric and is encouraged to practice persuasive writing as an academic pursuit. This very writing is an attempt at that.

In order to obtain any degree from a college or university, students must take Writing 122, or equivalent, as a core requirement. This is the course that supercharges basic writing composition into rhetorical argumentative writing. The University of Oregon describes their WR122 course “Written Reasoning as a Process of Argument”[3] as follows:

“WR 122 focuses on specific ways to develop argumentative essays in response to the challenges of complex contexts, which should include increasingly sophisticated competing arguments and issues… Students practice further how to develop effective theses and compose essays in which they control the reasoning that supports their theses.”

And this is where the persuasion gets baked in. Every writer is taught how to sell their ideas to an audience through the use of effective persuasive communication. This is regardless of any motive, such as profits or an attempt to influence a campaign, and so on. Recognize that it can be assumed that everyone’s motives, even if their ideas are unpopular, are pure to them.

Maybe the witch is just misunderstood

In the Grimm’s Fairy Tale Hansel and Gretel, a witch lures children into her house for the express purpose of fattening them up in order to eat them. From the witches point of view, you can easily see that she is just looking out for “numero uno”, so her intent is more selfish. However, it is difficult to see her point-of-view when we live in society that has a “cultural truism” such that we don’t eat children.

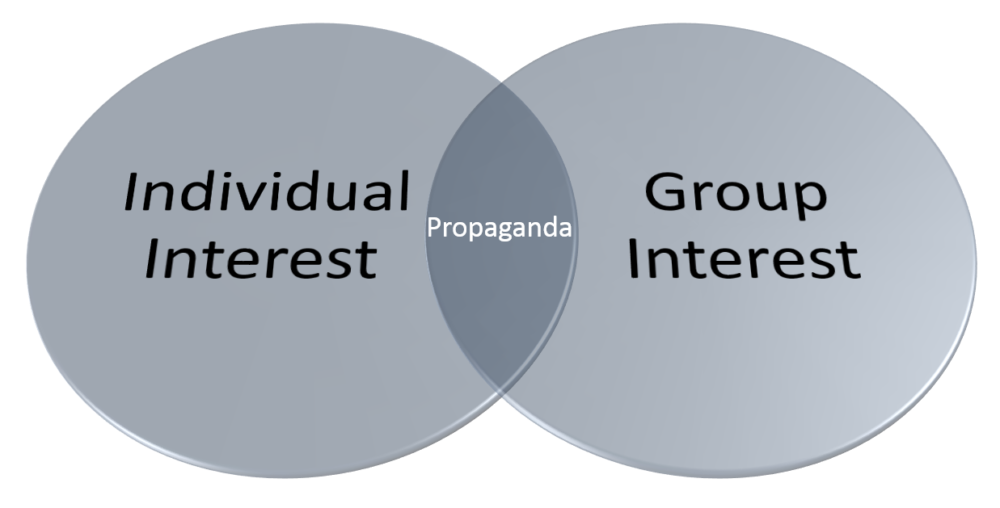

The witch doesn’t live in that society though. She lives in her world inside of a house made out of candy. She plays by a different set of rules. And it is at this intersection, between individual interest and group interest, that we see a lot of propaganda and counter-propaganda being used to sell ideas that recruit between each side.

Unpopular ideas are often the fault of bad rhetoric

In the marketplace of ideas, it is the best rhetoric that wins. The job of marketers, advertisers, and information brokers selling products, people, and ideas to the public is to use the best rhetoric at their disposal. To use all the wilds of communications to deliver their message. To the extent that unpopular ideas are sold back to us by these same peddlers as counter-propaganda, we can’t really know.

However, providing the rhetorical persuasive arguments for both sides is the ultimate application of what is taught because it controls the reasoning that supports the theses. Working both sides is the best propaganda.

In the fairy tale, the individual candy items aren’t responsible for the intent of the witch. They are like employees, just doing what they are told. They just happened to have had the misfortune of being employed by an old lady with a candy house she hunts with. An environment that allowed the best candy items in large quantities to flourish while at the same time supporting the witches agenda, hidden in plain sight. Oh, the sweet smell of success.

So there must be something about the environment. An environment of propaganda that is also, somehow, free of propaganda.

That’s next.

NOTES:

[1] “The Relative Efficacy of Various Types of Prior Belief-Defense in Producing Immunity Against Persuasion”, William J. McGuire, Demetrios Papageorgis, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 1961, Vol 62, No. 3 (1961), pp. 327-337

[2] “Rhetoric.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/rhetoric. Accessed 4 Nov. 2022.

[3] “WR 122: Written Reasoning as a Process of Argument” University of Oregon, Research Guides, https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/wr122. Accessed 4 Nov. 2022.